<< Back to Blog

Dylan Revisited: Highway 61 Revisited (1965)

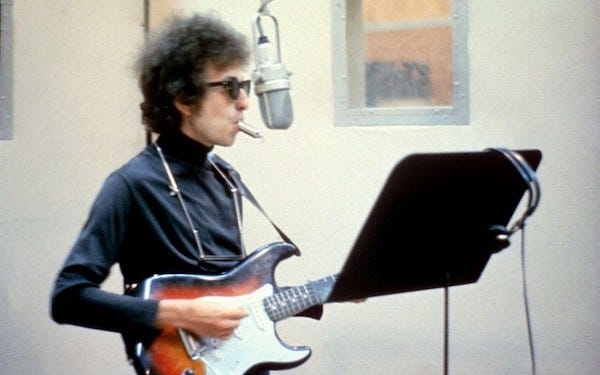

June 16, 1965. Session musician and songwriter Al Kooper is about to blag his way into rock history by playing an instrument he doesn’t even know how to turn on. Such is the unplanned majesty of Bob Dylan’s Like a Rolling Stone and the album it opens, Highway 61 Revisited.

Producer Tom Wilson had invited Kooper along to watch the second day of Bob Dylan and his band attempting to record an unusual and awkward new song. But the ambitious Kooper had no intention of sitting on the sidelines behind the glass and instead sidled in among the musicians.

When Wilson moved Paul Griffin from the Hammond organ to piano, Kooper filled the vacated seat, relieved that Griffin had left the power on. Despite being unfamiliar with his instrument and the song he was about to play, Al Kooper turned out to be one hell of an organ player.

On hearing the playback, Dylan asked Wilson to bring up the organ part. The producer, who had been surprised to spot Kooper by the organ, dismissed the suggestion saying, “That guy isn’t an organ player.” Dylan replied, “Don’t tell me who is an organ player and who isn’t.”

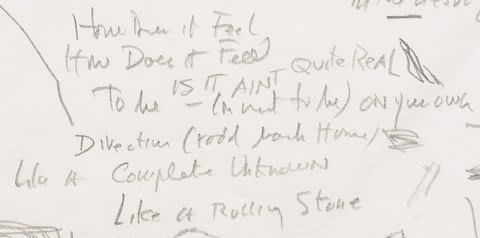

What Dylan heard in Kooper’s playing was a solution to capturing the essence of a song that had been problematic since its inception. He’d later describe the original unedited lyrics as “a long piece of vomit”. Those words he spewed would prove extremely significant.

In the aftermath of his exhausting 1965 world tour that incorporated the slow disintegration of his relationship with Joan Baez and interminable prickly press conferences about his status as a protest icon, Dylan was considering quitting his chosen career.

Writing Like a Rolling Stone and expelling his bitterness, contempt and cruelty onto the page helped to restore his enthusiasm for songwriting. He hadn’t thought of those retching words as a song until one day he felt the line “how does it feel?” sing to him from the page.

Those four simple words – and Dylan’s indignant delivery of them – became the hook that turned an unorthodox song into an iconic and culture-shifting hit. Mid-60s popular music was largely about love and longing. No one wrote songs that sneered and disdained like this.

Never mind the bile-soaked lyrics, Like a Rolling Stone is six minutes long – twice the length of the typical radio hit. Dylan’s record label Columbia refused to even countenance releasing it as a single. It simply didn’t make any sense.

But then an acetate copy found its way into the hands of a DJ at a New York nightclub. The enraptured crowd requested it again and again until the grooves wore out. The following morning, radio stations bombarded Columbia with requests for copies of Like a Rolling Stone.

Columbia eventually released Like a Rolling Stone with its six minutes split over both sides of the 7” vinyl. At first, radio DJs would just play one side until audiences realized there was more to the song and demanded the record be flipped.

Like a Rolling Stone reached no. 2 in the Billboard charts, becoming Dylan’s biggest hit so far. But its legacy would go much further, pushing pop music towards a harder sound and tougher themes, while disrupting industry norms and audience expectations.

Help by The Beatles kept Like a Rolling Stone off the top of the charts, but even Lennon and McCartney were in awe of Dylan. Of its startling opening snare shot, Bruce Springsteen said it “sounded like somebody’s kicked open a door to your mind.”

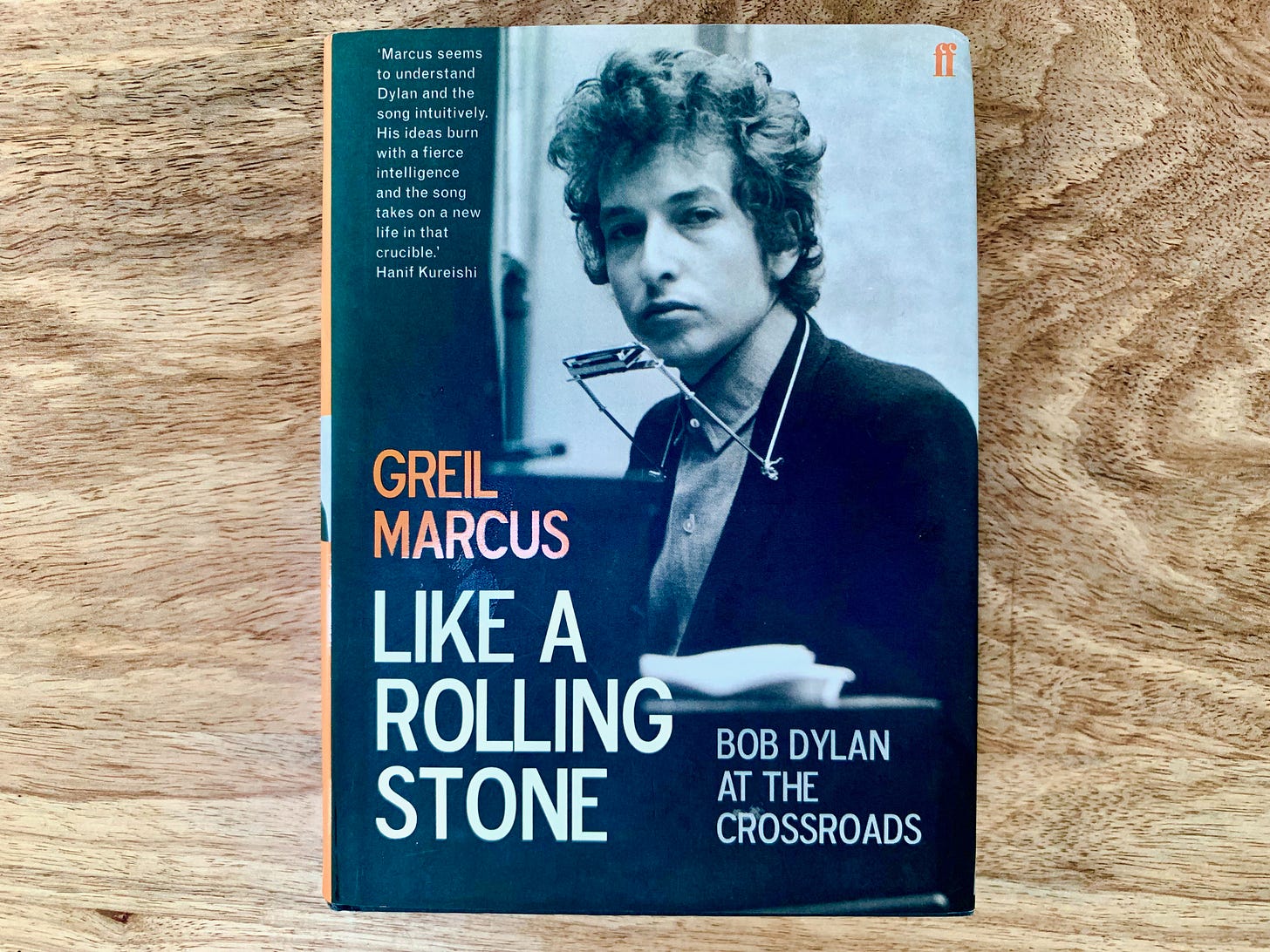

Yet it so very nearly didn’t happen. In his exhaustive book on the song, Greil Marcus writes that of the more than a dozen takes recorded over those two days in June 1965, none but the released master has the spark that makes Like a Rolling Stone such a special song.

And if Tom Wilson hadn’t shrugged “alright” after seeing Al Kooper behind the Hammond, Like a Rolling Stone wouldn’t have its unique trailing organ sound. Kooper’s ultra-improvised part acts a response to Dylan’s lyrical bile, tempering the haughty fury with a more relatable uncertainty that the impromptu player must have himself felt.

After his outsized impact on the final version of Like a Rolling Stone, Kooper became a key member of Dylan’s circle. He would make more significant contributions to the sound and style of Highway 61 Revisited, Dylan’s sixth studio album.

Before returning to the studio, Kooper joined Dylan at the 1965 Newport Festival. There he endured the boos as part of the band that plugged in to perform Like a Rolling Stone, It Takes a Lot to Laugh… and that dynamite version of Maggie’s Farm.

If Kooper was not an organ player before Like a Rolling Stone, now he very much was. He recalled how he and Dylan would find records that aped the sound of their song and laugh at hearing seasoned organists attempting to emulate Kooper’s unrehearsed style.

Kooper again applied his unconventional approach on Ballad of a Thin Man. He fills the song’s spaces with disorienting stabs and swirls on the organ that perfectly complement the foreboding chords from Dylan’s piano.

Ballad of a Thin Man’s lyrics reflect Dylan’s recent experience of chronic press conferences. It’s a vicious portrait of a hackneyed journalist whose only response to the inventive and imaginative is to ask who, what, when, where and how, but rarely why.

Kooper switches to the piano for Highway 61 Revisited’s title track, though his real contribution is the wild siren sound that opens the song. It’s a toy police whistle that he carried with him to scare his pot-smoking friends into thinking they were about to get busted.

On the Cutting Edge collection, you can hear the take when the whistle is introduced and Dylan’s response is to break down into laughter. You can also hear how earlier versions without the whistle lack the insanity inherent in the song’s lyrics.

Highway 61 Revisited is a cavalcade of chancers, cheats and ne’er-do-wells, whose every scam and deception takes place on the titular road. Start a verse with the line “Mack the Finger said to Louie the King” and you have my undivided attention.

Most of all, I remember being awe-stuck on first hearing Dylan audaciously flip the bible story of Abraham sacrificing his son. He turns a momentous display of power and magnanimity into a cheap hustle by a strongarming deity.

The real U.S. Route 61 starts in Dylan’s home state of Minnesota and follows the Mississippi south to Louisiana. It was the conduit for blues music as it spread north, spawning rock’n’roll and eventually lending to the title of Dylan’s first true rock record.

It is said that legendary bluesman Robert Johnson went down to a crossroads on Highway 61 and sold his soul to the devil in exchange for his extraordinary guitar skills. One of Johnson’s musical successors flaunts his own talent all over Dylan’s titular record.

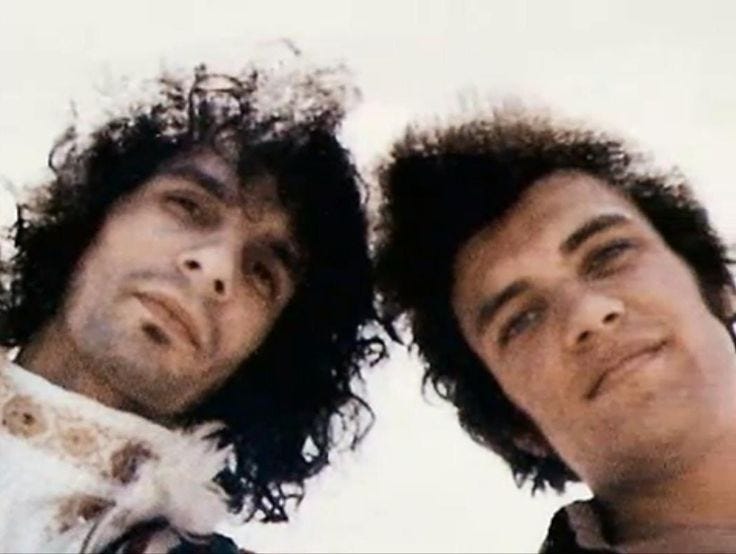

Mike Bloomfield adds to mayhem of the song Highway 61 Revisited with injections of woozy surf rock guitar licks. Al Kooper was initially annoyed to encounter Bloomfield’s talent during the Like a Rolling Stone sessions.

Before Kooper sneaked in to a seat behind the Hammond organ, he first tried out on guitar. After all, that was more his instrument than the organ. But then Mike Bloomfield arrived and Kooper abandoned any hope of being Bob Dylan’s new guitarist.

As soon as Bloomfield started to play, Kooper realised that The Paul Butterworth Blues Band guitarist was streets ahead of him. So Kooper retreated back behind the glass and waited for his next opportunity, while Bloomfield impressed more than just the hopeful usurper.

Bob Dylan was very excited about Mike Bloomfield. In an outtake for the unused song Sitting on a Barbed Wire Fence, he sings of the sometime object of his desire that “she ain’t as good as this guitar player I got right now”.

Bloomfield proved his worth on Like a Rolling Stone and even relegated another guitar star, Bruce Langhorne, to playing tambourine. Dylan then recruited Bloomfield for his electric Newport band before inviting the guitarist to join the sessions for his next album.

Though Highway 61 Revisited is Dylan’s first true rock’n’roll album, guitars are rarely the star. Even the most straightforward 12-bar blues song, From a Buick 6, is largely driven by Harvey Brooks’ incredible bass line.

Bloomfield’s guitar solos are overpowered by Dylan’s harmonica but he’s doing sterling work throughout. From a Buick 6 is about a strong, dependable, earthy woman – likely Dylan’s future wife, Sara Lownds, who may not have appreciated her walk being compared to Bo Diddley’s.

Bloomfield does get his chance to shine on the album’s second song – the one unenviably tasked with following up Like a Rolling Stone. This is not a problem for the guitarist whose unleashes scorching solos after each chorus of Tombstone Blues.

Bloomfield is more than aided by Bobby Gregg’s drums, which are military-tight and relentlessly propel Tombstone Blues forward. Dylan would later say that nothing like the song had ever been done before.

I had certainly never heard a sentence as acutely oblique as “The geometry of innocent flesh on the bone”. Or as comically Orwellian as “the sun’s not yellow, it’s chicken”. And I just adore that final verse about easing “the pain of your useless and pointless knowledge”.

Dylan asked Mike Bloomfield to join him on tour but the guitarist decided to stick with The Paul Butterfield Blues Band. He soon grew weary of that band’s relentless schedule and left to form his own group, Electric Flag, which included Harvey Brooks on bass.

Electric Flag didn’t last long and Bloomfield spent the next decade flitting between various short-lived projects. Plagued by insomnia and increasing drug use, he became erratic and unreliable, walking out on an Al Kooper collaboration after just one session.

By the late 70s, this prodigious talent was a recluse reduced to writing porn movie scores. In 1981, less than a year after rejoining Dylan for a live show in San Francisco, Mike Bloomfield was found dead in his car after an accidental overdose of cocaine and methamphetamine.

Dylan would move on to longer lasting collaborations with other great guitarists, including an unexpected encounter as he was working on Highway 61 Revisited’s lengthy closing song. On the third day of trying to record Desolation Row, producer Bob Johnston invited a friend from Nashville to the studio. Charlie McCoy would give the song an unexpected sprinkle of magic.

Johnston himself was an out-of-the-blue presence when Dylan arrived at Studio A to begin recording Highway 61 Revisited. Tom Wilson – who had worked with Dylan since the Freewheelin’ and as recently as the Like a Rolling Stone sessions – was suddenly no longer at the controls.

According to Dylan, he was as surprised as anyone to see Johnston instead of Wilson. But it’s inconceivable that his manager Al Grossman would have arranged a change of producer – as when Wilson took over from John Hammond – without Dylan’s consent.

Johnston’s studio style was very laid back. Al Kooper described him as “invisible”. Though he was a songwriter himself, who had several songs feature in Elvis movies, his remit here was simply to get out of Dylan’s way.

Even so, he made a major contribution to the sound of Desolation Row. According to McCoy, Johnston had promised him Broadway tickets if he was ever in New York. After arriving in the city, McCoy phoned to enquire about those tickets and was told to come to the studio.

Johnston introduced McCoy to Dylan, who suggested he play guitar on a song he was about to record. McCoy was surprised – he didn’t particularly think of himself as a great guitar player – but his Spanish-flavoured fills gave Desolation Row fresh texture and drama.

When Dylan played Desolation Row solo during his next tour, it remained enthralling. But McCoy’s guitar adds impetus to this epic – even if he slightly runs out of steam after some particularly pleasing licks around the five-minute mark.

For the first time since his debut, this is a Bob Dylan record without an obvious protest song. While Desolation Row’s harried characters and titular setting speak of a world gone wrong, Dylan’s not taking sides or pointing fingers.

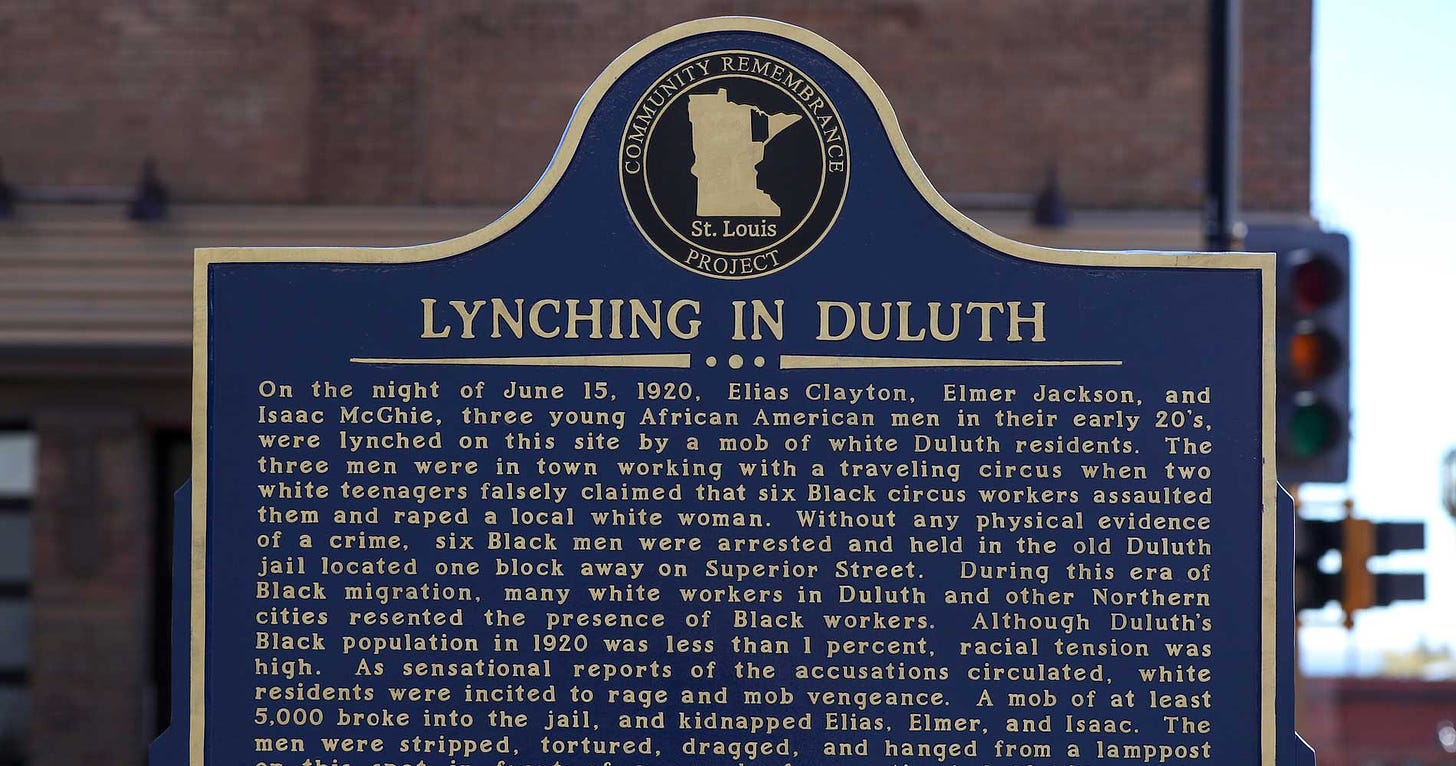

Yet the opening line – “They’re selling postcards of the hanging” – likely references an actual lynching that happened in Dylan’s birthtown of Duluth in the 1920s. This suggests that the injustice and cruelty of the song’s imaginary world is rooted in Dylan’s – and our – real one, placing Desolation Row in the realm of protest song.

It’s not purely a desolate place. It’s also sleazy, thrilling, intriguing and potentially pleasurable. Al Kooper suggested that the real Desolation Row was New York’s 8th Avenue – then a seedy hub for drugs, porn and prostitutes.

What these different readings indicate is that Desolation Row is, above all else, a fully realized world. It’s one you dive headlong into on hearing that opening strum and only emerge from – somewhat sore and soiled yet satisfied – at that closing harmonica blare.

It’s a songwriting achievement every bit as remarkable as A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall or It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding). And, like so much of the rest of Highway 61 Revisited, one that was attained through impulsive decisions and application of talent, as well as Dylan’s hard craft. Yet amid all the spontaneity, Dylan also brought a new meticulousness to the studio.

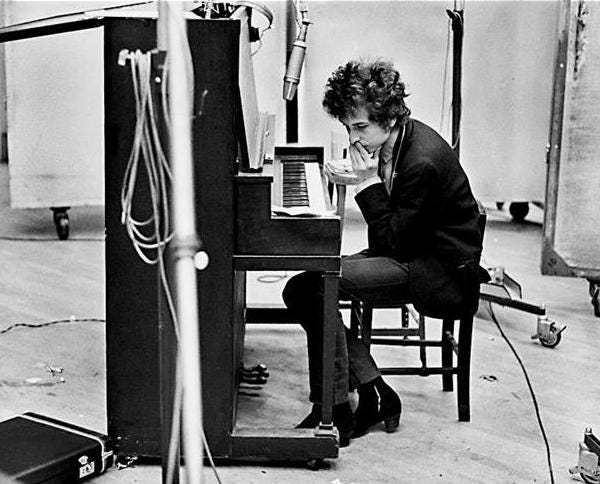

It’s lunchtime at Columbia’s Studio A and while the musicians are taking a well-earned break, Bob Dylan is working at the piano. By the end of the hour, he has transformed a song once called Phantom Engineer into one of Highway 61 Revisited’s most captivating moments.

Dylan and his band had originally attempted Phantom Engineer during the Like a Rolling Stone sessions a month previously. Then it was a taut, bluesy number. At Newport, it was loud and spiky.

But four days on from that controversial festival appearance, Dylan had completely revised the song and changed its name to the even more enigmatic, It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry.

The result is a wonderful slice of drawling Southern blues with a barnstorming barrelhouse piano from Paul Griffin and an outstanding harmonica solo. It Takes a Lot to Laugh… also has one of my favourite Dylan vocals and I just love singing along.

If Dylan was often flying by the seat of pants while recording Highway 61 Revisited, there was also a lot more deliberation than usual. In the past, he rarely did more than a few takes of a song. Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues took 16.

Over a long session, Dylan methodically arrived at a band setup that captured the song’s hazy disquiet. By the final master take, he had two pianists: Al Kooper tapping out fragile melodies on an electric piano; Paul Griffin adding atmosphere with his tack piano hammering.

Tom Thumb’s Blues is another unnerving world populated by inscrutable characters and perplexing situations. Being lost in Juarez is not where the narrator wants to be but, as the listener, I cannot help but be thrilled every time I’m returned to this nightmare.

Of Bob Dylan’s many songs, Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues is the one that resides most completely in my subconscious. I used to sing it repeatedly to my kids when they were restless, small-hour babies. Though I’m not sure why I thought this unsettling lyric was lullaby material.

Though Dylan had more of a process on Highway 61 Revisited, it was hardly painstaking. On Queen Jane Approximately, Mike Bloomfield’s guitar is obviously out of tune. But this – the last of the song’s seven takes – was deemed good enough for the record.

Queen Jane could be addressed to the same lost soul that features in Like a Rolling Stone, but the tone and approach here is completely different. Instead of bitterness and spite, Dylan is empathetic and open – “won’t you come see me?”

In Highway 61 Revisited’s crowded world of rancor, cynicism and incongruity, there is still room for a kind word. There’s still that undercurrent of vulnerability that Kooper brought to Like a Rolling Stone.

Queen Jane Approximately seems to be widely regarded as the weakest song on Highway 61 Revisited. I love it. And once again, Al Kooper is pulling up trees on the organ.

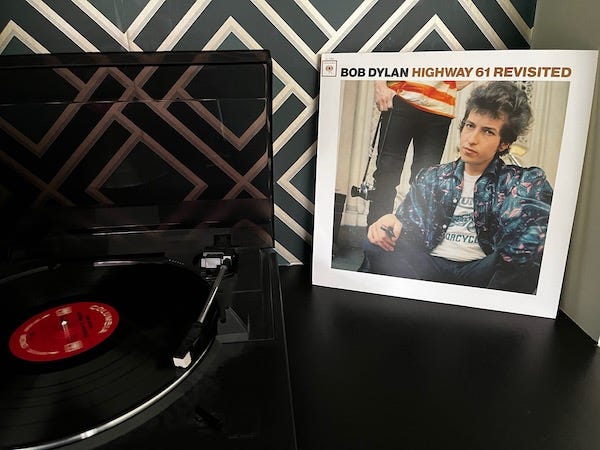

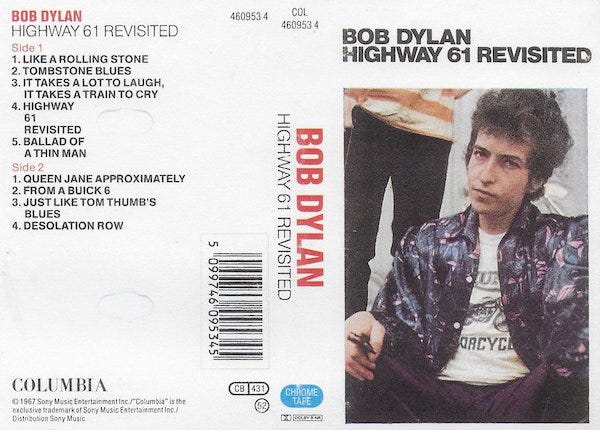

Highway 61 Revisited was the first Bob Dylan album I bought for myself. I was with my neighbors, who offered to play my cassette during the car ride home. Reluctantly I handed it over. A couple of songs in, they quietly ejected the tape. Turns out Dylan’s not for everyone.

I was glad, as I wanted my first full listen to this record to be my own with noone else intruding on the experience. On arriving home, I put the cassette in my Walkman, donned those orange foam headphones and sunk into Dylan’s world.

Since those teenage days, Highway 61 Revisited has – more than any other record by any other artist – been a constant in my life. Everyone else can argue about where it sits in the Dylan canon, but I know that it’s the most important record in my world.

What do you think of Highway 61 Revisited? Let’s start that debate about its place among the greats.