<< Back to Blog

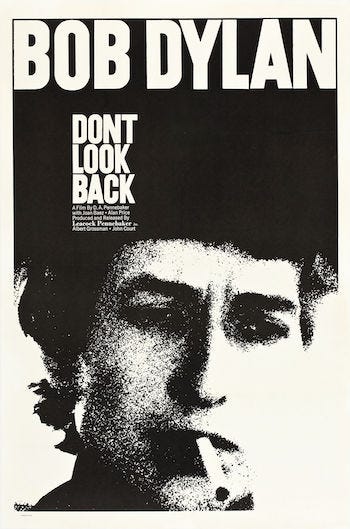

Dylan Revisited: Dont Look Back (1967)

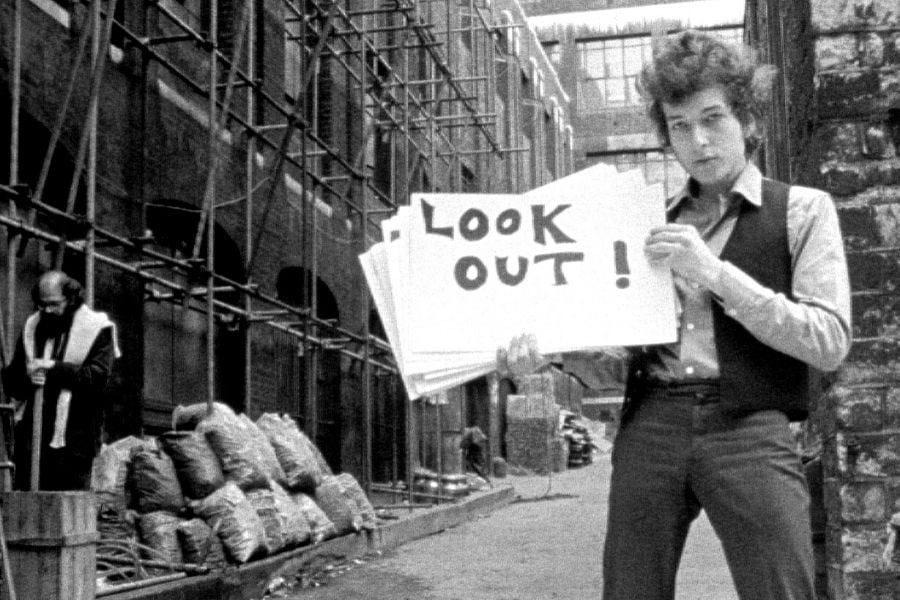

Dont Look Back – D.A. Pennebaker’s documentary about Bob Dylan’s 1965 UK tour – starts with the famous cue card promo for Subterranean Homesick Blues. The director wanted to “set the stage” for Dylan. Yet for the rest of film, his main character shares the spotlight.

In the film’s next scene, while Dylan is quietly rehearsing backstage, we briefly see his manager, Al Grossman. For anyone familiar with this pivotal but often enigmatic figure in Dylan’s story, this glimpse is thrilling.

Let’s start with his lush cardigan – Grossman’s a smart guy who knew how to dress for the English weather. And for the occasion: when later the tour arrives at London’s Royal Albert Hall, the manager has ditched his cardi for a smart three-piece suit.

The real fun starts when a hotel manager appears in Dylan’s room to complain about the noise. At first, Grossman is evasive but polite. But he soon explodes with rage at the officious clerk, issuing insults and threats.

The key insight into Al Grossman comes in a classic scene that should be part of every business school curriculum. Dylan’s manager and London-based talent agent Tito Burns are negotiating a deal with two of the UK’s big television producers.

Burns is playing the BBC and Granada against each other, saying “I know there’s 1500”. “Why not ask for 2?” replies Grossman. When the Beeb lowballs them, Grossman takes over and does a wonderful impression of being wounded by the offer.

Burns uses the word “truthfully” in one breath then next assures his contact that he’ll be seeing Mr. Grossman in 10 minutes, while Al smiles in the seat opposite him. Unsurprisingly, Burns was not impressed with his brinkmanship and duplicity being shown on screen.

Another man who knows all about underhand music business shenanigans is Alan Price. Having pissed off his bandmates by claiming sole credit of and therefore royalties for House of Rising Sun, Price is an ex-Animal, now just hanging out with Dylan and his entourage.

And drinking a lot. Price enjoys a vodka’n’tonic by taking sips from separate bottles then mixing the results in his mouth. Later, he’ll open a beer bottle off the edge of a piano though this moment of petulance may have been the result of a cutting Dylan question.

Price had been in an upbeat mood, playing some George Formby on the piano before getting laughs for his slow-motion impression of Herman’s Hermits singer Peter Noone. Then Dylan asks if he still plays with The Animals and you’ve never seen a man deflate so quickly.

Did Dylan deliberately demean Price? It wouldn’t be the first time the star put someone in their place. Joan Baez had joined the tour assuming she’d share some stage time with Dylan, like at the Philharmonic Hall the previous October.

But she soon finds herself sidelined and we witness an early unintended humiliation by a photographer who takes her picture because she’s one of Dylan’s entourage not because he recognizes her.

Later, we watch Baez in the back of car as a glowing Dylan review is read out loud. Her face remains impassive as she munches on an apple, but you sense the envy and ego of a performer who is denied the spotlight she craves.

Despite all this, Baez remains an engaging, funny and kind presence. When that ignorant photographer asks her to pose for him, she pulls silly faces and tries out an English accent

In the back of another car, eating a different piece of fruit, she sings her own private version of It’s All Over Now Baby Blue: “crying like a banana in a sun”.

There’s also a lovely outtake where she meets a family of travellers at a petrol station. After giving them a bag of fruit, she offers to introduce them to Dylan when she discovers that the father is a fan.

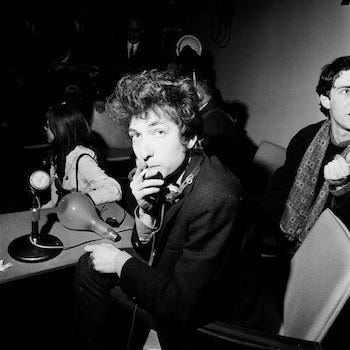

In the film’s early press conference scene, we see Dylan answering a barrage of inane questions, before Pennebaker cuts to Joan Baez singing, reminding us why this circus is in town.

The filmmaker wasn’t all that interested in songs when he made Dont Look Back. He viewed Dylan as a poet first and was interested in capturing the man more than the musical performances.

Most of the concert footage in the film is short, from the 45 seconds of All I Really Wanna Do that soundtracks the opening credits to the three songs cut together in just six minutes towards the end.

Perhaps the filmmaker was simply taking his cues from his subject. Dylan would later admit that by 1965 he had lost interest in many of the songs he was performing, as suggested by his rush to get through The Times They Are a-Changin’.

If Pennebaker preferred story over performance, he also understood that the off-stage songs had narrative value. The film includes a wonderful scene where Joan Baez plays Percy’s Song while its author taps out new creations on his typewriter.

Next, Baez sings Dylan’s incomplete composition Love is Just a Four-Letter Word while an engrossed Al Grossman watches on. “Do you have any more?” she asks Dylan. “I didn’t finish it” he replies before returning to his latest piece.

Then Dylan picks up the guitar and plays two Hank Williams songs, Lost Highway and I’m So Lonesome I Could Die. Hilariously, Bob Neuwirth has to remind him of the opening line from the former: “I’m a rolling stone, all alone and lost”.

Later, we get that celebrated scene where English folk singer Donovan – introduced at the very start of the film as a potential Dylan rival – plays him his song To Sing for You.

At one point, Dylan says “that’s a good song man”. But as this praise comes right after the banal “I’ll sing a song for you / that’s what I’m here to do” chorus couplet, it’s possible he was being sarcastic.

When he’s done, Dylan takes over and – at Donovan’s request – plays It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue. Any notions about Donovan being close to Dylan’s level are blown away by that performance and you suspect that Dylan knows it.

Dylan brings up his now-vanquished rival at the Royal Albert Hall during his performance of Talkin’ World War III Blues, ad-libbing “I looked in the closet / there was Donovan”.

Subscribed

We also see Dylan perform It’s Alright Ma and Gates of Eden at the Royal Albert, two songs he’s presumably more interested in singing than the old finger-pointing stuff. But Pennebaker doesn’t give us much more than a few minutes of these epic songs.

Yet there is one moment when the filmmaker is content to step back and let Dylan the live performer have his moment. Pennebaker’s camera and cutting blade scarcely move for a compelling near-complete take of The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll.

This scene sums up a lot about Pennebaker’s filmmaking: from his unobtrusive camera work to his astute decision making in the edit suite.

In 2014, Dont Look Back was named the ninth best documentary feature of all time by Sight & Sound magazine, deservedly placing it alongside the field’s most innovative and important works.

With Dont Look Back, Pennebaker transformed the idea of a music film. Instead of documenting a performance, compiling a jukebox musical or even just creating a standard puff piece, Pennebaker embeds the viewer deep inside Bob Dylan’s world.

He achieves this by making the apparatus of filmmaking as unintrusive as possible. Pennebaker shot the footage using a small handheld 16mm camera with no additional lighting and sound captured directly on a single mic (aside from the concert scenes).

The price of feeling like a member of Dylan’s entourage is context. Nobody explains anything to you. No voiceover sets the scene, no contemporary talking heads explain what just happened. You’re outside the window, watching things happen. Figure it out later.

This deliberate strategy was new, especially in the world of music. Al Grossman invited Pennebaker on the tour, assuming he’d capture some useful promotional material. But the filmmaker wasn’t interested in what the manager of a recording artist wanted.

Instead, we overhear a Guardian journalist file his copy over the telephone (which, when viewed today, feels like a vital document of a dead art). The man’s patronising review says more about the media’s timeless need for a hot take than it does about Bob Dylan or his music.

In a scene that surely inspired This Is Spinal Tap, we follow Dylan and his crew try to find the exit of Manchester’s Free Trade Hall after a show. I love that you can hear God Save the Queen blaring out back in the main arena, as the musician stumbles through the backstage half-light.

As noted above, Dylan was now bored by songs like The Times They Are a-Changin’. Instead, Pennebaker unearths excitement watching the stagehands resolve a problem with the sound while Dylan drones away about senators and congressmen in the background.

Though Pennebaker wasn’t too interested in Dylan’s music, he still knew how to use it to great effect. An onstage performance of Don’t Think Twice quickly cuts to a view from a train, the pace of the passing houses beautifully matching the rhythm of the song.

From these images of grim and grey 1960’s English suburbia, Pennebaker cuts to Dylan. The singer is on that train, rubbing his eyes, looking as exhausted as the tired country outside the window.

At the conclusion of the three-song supercut from the Royal Albert Hall, Pennebaker’s camera leans back as Dylan leaves the stage. He focuses on a pair of spotlights, still illuminating the empty space Dylan has vacated, just in case he might return.

This gravitational pull of stardom is the heart of film. Pennebaker is most interested in all those people drawn into Dylan’s orbit. Everyone who wants their own piece – a quote or an autograph, a moment or money – of this one man.

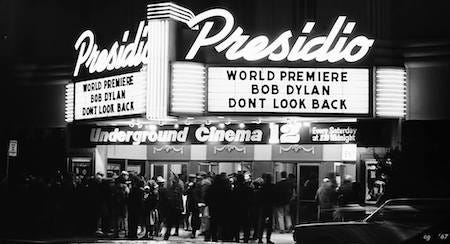

Remarkably, Pennebaker found it difficult to find a distributer for the ninth best documentary of all time. The format of his film was so different, so inventive, nobody wanted to touch it. Even though it’s about one of the era’s most iconic figures.

Dont Back Look finally hit screens in 1967 when Bob Dylan was very different from the character depicted in the film. But it helped make this version of Dylan iconic.

Who is this character that Pennebaker captured before the boos and bike crash? And does the film hint at the transformations to come?

First off, Dylan is funny. His responses to the barrage of often weird questions from journalists are witty, surreal, cutting and playful. Though it’s not that he doesn’t take himself seriously. He just has very little regard for the hacks surrounding him.

Dylan uses humour to avoid having to be honest. Even to the point of bringing along an oversized prop so when he’s earnestly asked about his real message, he can quip: “Keep a good head and always carry a lightbulb.”

Bluster is another tool in Dylan’s defensive arsenal. When a fan asks if he’s religious, his response is derisive, almost grandstanding in its delivery. He even paraphrases his own lyrics: “nothing is sacred”.

Pennebaker provides a contrast to this side of Dylan in Dont Look Back’s one moment of backstory. After a BBC journalist – with one of the few thoughtful and well-phrased questions we see – asks how he got started, the film cuts to 1963 footage of Dylan playing Only a Pawn in their Game at a rally in Mississippi.

Wearing a simple shirt, earnestly singing in a rural setting, he appears to be a very different character. But his evolution never stops, so we are soon back in England with the leather-jacketed Dylan telling us that times are a-changin’.

This Dylan is starting to reject that old version of himself. When Grossman tells him that The Freewheelin’ album has won a folk music award, Dylan suggests that they “give it to Donovan”.

His playfulness has a dark side, like when his verbal sparring with Terry Ellis (future founder of Chrysalis Records and Jethro Tull manager) turns into a vicious battle. Dylan’s pummels Ellis with his questions until the latter trips himself up to the singer’s GOTCHA delight.

That scene is a marked contrast to Dylan’s meeting with the High Sheriff’s Lady, a fur-coated posh woman with three gormless sons, to whom he is polite and charming.

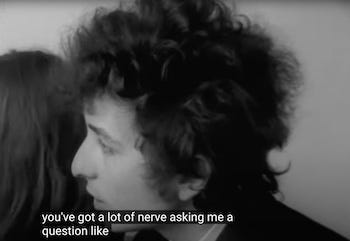

Dylan’s good manners rarely extend to the press and one of the film’s climatic scenes is an angry confrontation with a TIME journalist.

Dismissing the publication, Dylan sounds like a modern-day anti-MSM keyboard warrior, saying “they got too much to lose by printing the truth”. When asked what the truth would look like, he answers “a tramp vomiting in the sewer” then later adds “you have no ideas, just facts”.

It’s Dylan at his most arrogant, unpleasant and immature. The final insult comes when the TIME man asks “Do you care about what you sing?” Dylan’s response includes a familiar phrase: “You got a lot of nerve asking me a question like that”.

But just as suddenly, the sly humour returns as he claims to be “just as good a singer as Caruso…you just have to listen closely”. The 1965 UK tour Bob Dylan is impossible to pin down. It’s a trait he’ll never lose.

In amongst all the confrontation and bluster, Dont Look Back offers a few moments of real insight. At one point Dylan says that he “not trying to get anybody to listen”, which feels like a genuine statement in light of the subsequent years of following his own path.

When asked about his songwriting, Dylan says “I can’t turn it off”. The film’s 1967 audience won’t yet have the evidence of The Basement Tapes to demonstrate just how true that statement is.

As he leaves the Royal Albert Hall, Al Grossman tells his charge that the press has “started calling you an anarchist, because you don’t offer solutions”. Dylan’s response: “Well, give the anarchist a cigarette”.

I love this line as the ultimate summation of this Bob Dylan. Dont Look Back shows us all these people trying to explain him, but he is mostly uninterested in their definitions and labels.

As the film’s title suggests, Dylan will keep on keeping on. Even this masterful portrait of him will be out of date by the time people first see it. But that won’t stop me watching Dont Look Back again and again.