<< Back to Blog

Dylan Revisited: Bringing It All Back Home (1965)

In late 1964, Bob Dylan heard I Wanna Hold Your Hand by The Beatles and decided he wanted some of that for his next album, Bringing It All Back Home. But that didn’t mean he was coveting a number one or itching to plug his guitar into an amp and play some rock’n’roll.

When Dylan heard Lennon and McCartney’s chart-topping single, what he craved more than anything was a sense of hand-holding harmony. The solo artist listened to the way the Liverpudlians blended their voices, to the band’s tight combination of rhythm and melody and decided this is what he wanted to do next.

Then comes the story we all know. Dylan went electric on Bringing It All Back Home, a bunch of people booed his live shows and popular music was never the same again. Except it’s not quite as straightforward as that.

For a start, Dylan already had a harmonic partner, someone he was holding hands with both musically and romantically. I recently revisited The Bootleg Series Vol. 6, where Joan Baez joined Dylan on stage at New York’s Philharmonic Hall for four songs.

The pair were the unofficial king and queen of the folk scene. But listening to the show now, you can sense that Dylan was tiring of Baez. Though she accompanied him on a UK tour the following year, the pair no longer shared the stage and she later admitted that she had “no idea what I was doing there”.

Joan Baez represented what Dylan was keen to leave behind: folk music, protest songs and being a chosen one. At the Philharmonic, he played new material that signaled his new direction – though the most significant of these songs was not one of Bringing It All Back Home’s electric shockers.

Dylan had composed Mr. Tambourine Man early in 1964, whilst on a road trip across the US. He attempted to record it during the Another Side of Bob Dylan session in June, bringing in Ramblin’ Jack Elliott to harmonize with him.

Elliott didn’t know many of the words and the attempt to record Mr. Tambourine Man was abandoned after one take. Dylan realized that he wasn’t quite ready to immortalize what he believed was the first song he had written that was truly his and not what others expected from him.

By January 1965, Dylan was finally ready to record Mr. Tambourine Man. Though it appears on Bringing It All Back Home’s “acoustic” side, this isn’t a solo version like he played at the Philharmonic or on his Witmark demo.

Guitarist Bruce Langhorne was well known for also playing a large jangling frame drum, particularly when recording with Richard and Mimi Fariña (Joan Baez’s younger sister). And this is who Dylan asked to provide electric harmonies when recording Mr. Tambourine Man.

Langhorne’s twinkling electric guitar sprinkles additional magic on a song already infused with the surreal and fantastic. In his retreat from prosaic protest, Dylan winds up in a world of poetic wonders where sound matters more than meaning.

Wisps of words accumulate one after the other, forming hazy images that drift apart and collect into something new. Mr. Tambourine Man is a song of sensation above sense. One more concerned with the signifier than the signified

If Dylan’s previous songs were out there blowin’ in the wind and he was merely the one who captured them, Mr. Tambourine Man could only have been written by him. It signals a new internal focus, though one ultimately best expressed by the addition of external collaborators.

One of these outsiders was not a musician that Dylan’s producer Tom Wilson invited to help bring fresh harmony to Bob Dylan’s songs on the second day of the Bringing It All Back Home sessions.

He was a Dylan contemporary who pioneered the narrative of being previously noted for playing acoustic guitar before meeting a talented Canadian rhythm’n’blues group called The Hawks and incorporating their electric sound into his music.

The singer who first drafted in Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm and Garth Hudson (along with another future Dylan collaborator, Mike Bloomfield) for his So Many Roads record was John Hammond Jr. Yes, the son of the man who signed Dylan to Columbia and produced his first album.

Though he fell out with the father, Bob Dylan was excited by what he heard from John Hammond Jr’s sessions with The Hawks. He also heard The Animals’ chart-topping electric version of his/Van Ronk’s arrangement of House of the Rising Sun around this time.

With all these outside influences, Dylan going electric seemed inevitable. His producer Tom Wilson began experimenting with electric overdubs on some of the singer’s older recordings and would later have a hit using this technique on Simon and Garfunkel’s Sound of Silence.

Yet, day one of the Bringing It All Back Home sessions was just Dylan in the studio with an acoustic guitar and a harmonica. Though he and Wilson recorded ten complete songs that day, none would feature on the final album.

Without ever appearing to openly discuss the idea with Dylan, Wilson invited musicians to the studio for the next session. They took on the songs attempted on the previous day and the results were transformative.

Like on Mr. Tambourine Man, Bruce Langhorne’s electric guitar noodling elevates the gorgeous She Belongs to Me. Whether it’s about a woman or Dylan’s own creativity, the title is ironic – this madame/muse belongs to no one.

Love Minus Zero/No Limits is in a similar vein with Dylan’s new backing band fleshing out the melody and adding gentle rhythm to a song that features some of his loveliest imagery.

Yet both these songs are not rock songs at heart and Dylan will largely play them acoustically at future live shows. She Belongs To Me opens the solo set that preceded the incendiary, “Judas”-inciting, noise fest that rocked the UK in 1966.

The fresh power of Dylan’s electric band can be fully appreciated on another song that was originally attempted acoustically. And it’s telling that a portion of that solo recording acts as an introduction to Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream.

When you hear Dylan strum his guitar and sing “I was riding on the Mayflower”, it sounds like he’s about to revisit his previous album’s Motorpsycho Nitemare. But it’s interrupted by Tom Wilson bursting into teary peals of laughter before saying “ok take 2”. And then the magic happens.

Bruce Langhorne would later call the full band studio performance of Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream as “a form of telepathy”. With little rehearsal, the musicians blazed their way through the song with instinctive rhythm and energy.

I’ve previously complained that Dylan’s studio recordings of his funny/talkin’ blues songs are weakened by the lack of audience feedback. Here the dynamism of the music, that funky piano and Langhorne’s relentless riffing, replicates the collective exuberance of a live performance.

Dylan himself seems greatly energized and he delivers each surreal image and goofy gag with gusto. The curiosity sparked by hearing John Hammond Jr. play with a band catches fire on Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream.

Plus, “call me if they die” is a killer joke. And so is the penultimate verse’s coin toss that “came up tails, it rhymed with sails”, when the more obvious echo is the narrator’s other option: “jail”.

For a song that thrived on a group performance, Dylan only ever played 115th Dream live once. But another of Bringing It All Back Home’s Side A songs would quickly become a live staple, as well as a riotous manifesto for the newly electric Bob Dylan.

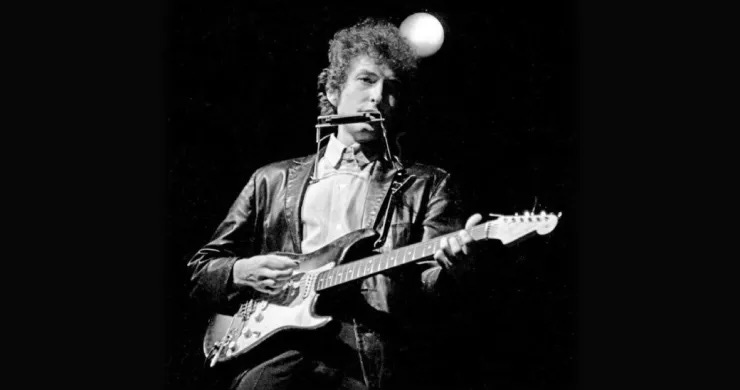

Newport Folk Festival. July 1965. A folk singer wearing a leather jacket and an electric guitar takes the stage. Behind him the drummer kickstarts a driving rhythm, a guitar wails and the singer steps to the microphone: “I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s farm no more”.

During the festival’s previous day, Bob Dylan had performed a well-received solo acoustic set, which included Bringing It All Back Home’s Love Minus Zero /No Limit.

But after hearing Newport organizer Alan Lomax disparage the electric sound of The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Dylan decided to go rogue. He recruited three members of Butterfield’s band, including Mike Bloomfield, guitarist on the recently recorded Like a Rolling Stone.

Along with another alum of that session, Al Kooper, Dylan’s spontaneously assembled band combusted on that Newport Folk Festival stage.

The unyielding beat laid down by drummer Sam Lay is almost martial. After Dylan bellows each line, Bloomfield unleashes wild guitar licks. It’s an aggressive, provocative performance met with the first of the boos that will follow Dylan around for the next year of his life.

The version of Maggie’s Farm on Bringing It All Back Home is tame by comparison. But unlike the unhappy members of the Newport audience, the album listener can actually hear the song’s words.

Behind Maggie’s Farm’s eccentric caricatures is a man who has had enough of being told what to do and who to be. Like in the jaded penultimate line: “they say sing while you slave and I just get bored.” Boredom being the hallmark of all forthcoming Dylan press conferences.

Perhaps it’s an overstatement to say that Maggie’s Farm was Dylan’s ultimate declaration on leaving the folk scene. But it’s certainly a song that is very significant for him and he has played it live more than a thousand times.

Dylan didn’t play Subterranean Homesick Blues live for more than 20 years after it opened Bringing It All Back Home in astonishing style. Drawing on Chuck Berry’s Too Much Monkey Business, the song was his first single to chart in the US.

As the album opener, Subterranean Homesick Blues would have been many people’s first exposure to an electric Dylan. But the shock and awe surely stemmed from his urgent cavalcade of paranoid observations and unorthodox advice. Who’s even listening to the backing band?

When I first heard this song 30 years later, it still held its power to thrill. As a younger teenage, it was mind-expanding to hear the originator of so many similar wordy gems that I loved to learn off by heart, like REM’s End of the World.

Pouring over the lyrics of Subterranean Homesick Blues proved useful when I was once invited to help out a Japanese bar band whose singer didn’t know all the words, but noticed me singing along. I’m not sure the audience of Tokyo drinkers appreciated my drunken vocal roaring – but hey, people complain about Dylan’s voice too.

Two other songs from Bringing It All Back Home’s electric A-side never made the live transition. The Jack Kerouac-referencing On the Road Again took 17 takes over three sessions to nail, so perhaps it no surprise Dylan never played it again.

Outlaw Blues features the first harmonica overdub on a Bob Dylan recording. The song’s droning guitar foreshadows the (Andy Warhol-credited) work that producer Tom Wilson will do with The Velvet Underground on their 1966 debut.

For all the fuss made about the electric first half of Bringing It All Back Home, it does contain this pair of (for Dylan at least) more disposable moments. But flip the record and you dive right into the album’s most essential songs.

Bob Dylan said that Mr. Tambourine Man was the first song that truly came from inside him. It opens the (mostly) acoustic second half of Bringing It All Back Home, a side that also contains the first song he claims came from outside him.

At seven-and-a-half minutes, It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) is the longest song on the record, but – after one false start – Dylan nailed it in a single take. It was a fittingly fluid process for a song whose writing he described as like speaking in tongues.

Given how much Dylan packs into these lyrics, it’s always surprising to realize that It’s Alright Ma is not even longer. In an astonishing series of uncompromising statements, the singer castigates consumerism, capitalism, the moral majority, religion and more.

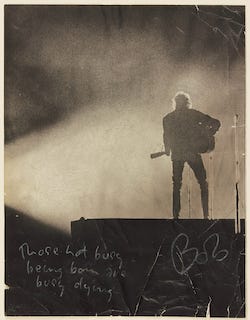

The song contains some of Dylan’s most iconic sentences like: “Even the president of the United States must sometimes have to stand naked.”; “Although the masters make the rules for the wise men and the fools.”; “He not busy being born is busy dyin’.”

My personal favorite is the couplet that leads to the final iteration of the famous “It’s alright, ma…” refrain. “And if my thought-dreams could be seen they’d probably put my head in a guillotine.”

This poetic appraisal of societal failings is set to a taut blues riff that recalls Highway 51 from his debut album, which itself references The Everly Brothers’ Wake Up Little Susie.

And, of course, the title alludes to another 1950s hit, Elvis Presley’s monumental That’s Alright Mama. Dylan said that when he first heard Elvis it was like “bustin’ out of jail.” On It’s Alright Ma, the shackles are well and truly off.

In between Mr. Tambourine Man and It’s Alright Ma is one of Dylan’s most surreal songs, the bafflingly brilliant Gates of Eden. Another track recorded in one take, its meandering flow of curious characters and images is strange yet satisfying.

If Tambourine Man came from inside Dylan and It’s Alright Ma was delivered by the muses, Gates of Eden is the product of pure graft. It’s Dylan adopting the cut-up technique of William Burroughs, throwing words in the air and working to make (some) sense of where they land.

The result is largely incomprehensible but nevertheless enthralling. And crucially, you can’t hear the labour. Dylan’s gift is to make Gates of Eden sound like free-flowing intoxicated babblings and not an exercise in surrealism.

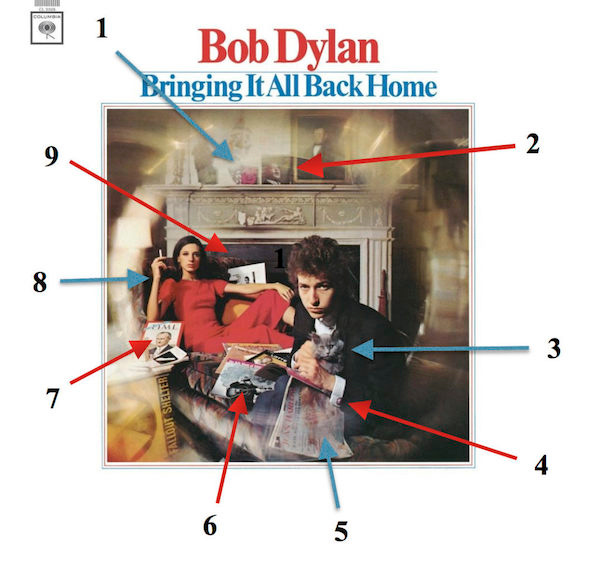

Before I get to the final song on side B of Bringing It All Back Home, it’s worth taking a closer look at one of the rock’s most annotated album covers.

Bob Dylan, a cat and a languid, smoking woman in red all stare at you through a fishbowl flare while your eye is drawn to the cultural detritus surrounding them. As a first impression of a record, there’s a lot to unpack in the cover art of Bringing It All Back Home.

Daniel Kramer talked his way into Bob Dylan’s life. After learning his trade as an assistant to the husband of acclaimed photographer Diane Arbus – who taught him to “open my eyes a bit wider” – Kramer became obsessed with photographing Dylan.

The photographer pestered Al Grossman’s office with phone calls until Dylan’s manager eventually relented and invited him up to Woodstock. Dylan had spent the summer of 1964 staying with Grossman in upstate New York, where Joan Baez recalled him “tapping relentlessly for hours” on a typewriter.

When he took a break to meet Kramer, Dylan at first displayed his usual initial coolness. But he quickly grew to like the photographer and soon asked him to shoot the cover for his new album.

Dylan’s record company Columbia wanted a big-name photographer, but Grossman fought for Kramer. The label finally agreed with one stipulation: the cover should feature Bob with a woman, like on The Freewheelin’.

Possibly because he was seeing both Joan Baez and future wife Sarah Lownds at the same time, Dylan didn’t want to be photographed with a girlfriend. Which is why Al Grossman’s wife, Sally, became immortalized as the impossibly cool woman on the cover.

The various magazines, records, books and artworks in the image were chosen by Dylan. Fans have catalogued and attempted to decode every item in the frame, so now we know that the chaise lounge was a wedding gift to the Grossmans from Mary Travers, of Peter, Paul and Mary.

Another gift were the cufflinks that Dylan wears, which Joan Baez mentions in her 1975 song Diamonds and Rust: “Ten years ago I bought you cufflinks, you brought me something”.

This dense, layered album cover image is a perfect introduction to Bringing It All Back Home. Its closing statement, It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue, is similarly apt. The last song recorded for the album is a fine and fitting farewell.

As with Another Side’s It Ain’t Me Babe, the song is about parting lovers. But it also feels like Dylan is speaking to more than just an individual. Whether directed at Joan Baez or the wider folk scene, the message encapsulated in the title is clear.

After being booed for his electric set at Newport Folk Festival, Dylan was persuaded back on stage. He regained the crowd’s adoration with an acoustic It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue – though given the song’s lyrics, he’s twisting the knife as he sings.

In one of the best scenes in DA Pennebaker’s doc Don’t Look Back, British folk star Donovan plays a song for Dylan. Bob responds with a scintillating version of Baby Blue, playing and singing like he’s putting his supposed rival firmly in his place.

It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue isn’t as treasured as Mr. Tambourine Man, as surreal as Gates of Eden or as caustic as It’s Alright Ma. Yet it manages to effortlessly combine a pinch of each of those songs into a cutting yet charming album closer.

This is the strength of Bringing It All Back Home. For all the invention, power and significance of its big statement songs (not to mention their greatness), it’s the sheer quality of some of the other tracks that make this record a true classic.

I always come back to the side A songs that spiritually belong on side B: She Belongs to Me and Love Minus Zero. Though a less significant part of Bringing It All Back Home’s story, they are the extraordinary beating heart that keeps this record returning to my turntable.

Bringing It all Back Home became the first Bob Dylan album to break the US Top 10 and kick-started his frenetic transition from protest icon to rock star. It’s the first part of Dylan’s mid-60s trilogy of extraordinary albums, but being mentioned in the same breath as Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde doesn’t diminish the outsized influence and impact of this remarkable record.