<< Back to Blog

Dylan Revisited: Bootleg Vol. 9 – Witmark Demos (1962-64)

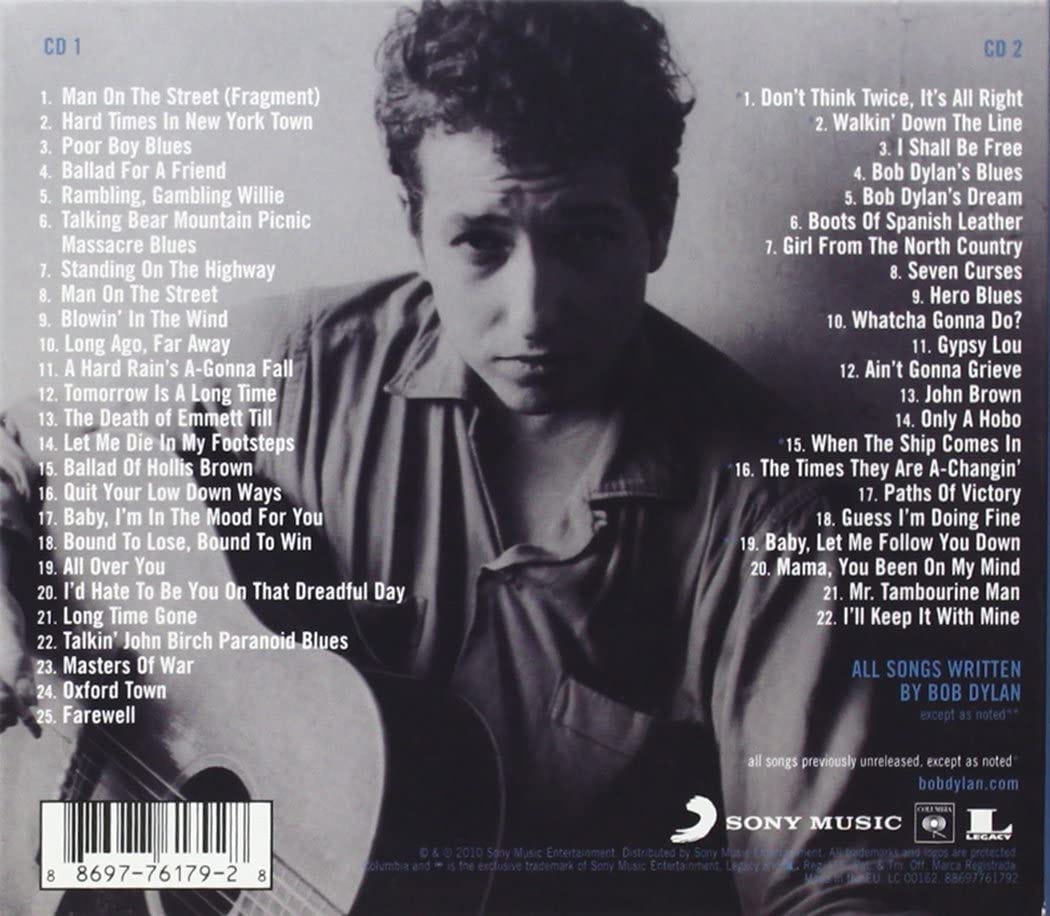

In my revisits to Bob Dylan’s first four studio records, early live sets and the first Bootleg volume, I’ve covered 55 original compositions, all written between 1961-64. But The Bootleg Series Vol. 9 – The Witmark Demos: 1962-64 unearths 15 new songs from that time.

When I revisited Bootleg vol. 1, I was impressed by the quality of the album outtakes and songs he only ever performed live. Bob Dylan’s cast offs are often superior to the best material of other artists. Does the same apply to his demos?

While Poor Boy Blues is credited as a Dylan original, it’s largely based on a Bo Weavil Jackson song of the same name from 1926. The jaunty guitar playing is quite different from Dylan’s usual style around this time.

Ballad for a Friend is a poignant song about the death of a friend. It’s set in the North County so has a sense of being autobiographical and Dylan’s lyrics capture the tragic ordinariness of road accidents.

Standing on the Highway is a fine fast-paced blues number that wouldn’t have sounded out of place on Bob Dylan’s debut album.

These three songs along with Rambling, Gambling Willie and Talkin’ Bear Mountain Picnic Massacre Blues were recorded in one session for Leeds Music Publishing.

Dylan also gave them the rights to Man on the Street – cut for, but not included on his debut album – and Hard Times in New York Town. Each of these last four songs had already featured on Vol. 1 of The Bootleg Series.

Some Dylan biographers suggest that the $500 (or $1000 – it’s a disputed amount) he received from the Leeds deal helped to spur on Dylan’s songwriting. For a man who spent a lot of time couch surfing, finally earning some decent money must have been a thrill and a serious incentive to keep creating new material.

Leeds didn’t make any money from the seven songs Dylan gave them. At least not until the songwriter’s new manager stepped in to buy out Dylan’s contract. Albert Grossman was keen to sign his man to another publisher, the Witmark of this compilation’s title.

After Bob Dylan fired Grossman in 1971, the Witmark deal emerged a major bone of contention. Dylan alleged that his manager had a secret stake in any money Witmark earned from his artists. Not only was Grossman splitting the contracted royalties with his songwriter, he was also earning a share of the publishing house’s income.

These allegations only came to light in 1981 after Grossman sued Dylan for not paying him the full amounts contractually owed to him. Dylan countersued and later claimed Grossman settled out of court. Others say that Dylan had to pay $2m to his former manager.

The first demo Dylan recorded for Witmark was this beautifully simple Blowin’ in the Wind. It’s no surprise Grossman rushed through the switch from Leeds by paying back the full value of the original deal. He knew he had a money-spinner on his hands.

Another likely financial winner was Tomorrow is a Long Time, a stunning love song with a keen sense of longing. Dylan decided against recording it during The Freewheelin’ sessions and the song was picked up by other artists.

Perhaps the most well-regarded is this gorgeous version by Judy Collins. Tomorrow is a Long Time has similarities with Seven Curses, which Dylan recorded for Witmark a year later and whose story draws on Collins’ song Anathea.

Tomorrow is a Long Time was also recorded by Rod Steward, Odetta (another Al Grossman artist) and Elvis Presley. Dylan said of the Elvis version, “it’s the one recording I treasure the most”.

In demoing Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues, Dylan plays around with some of the lyrics. He adlibs that the only people he can trust include “me…and Al Grossman”.

Perhaps Dylan should have been more paranoid when it came to his manager. Yet, according to Peter Yarrow (of Peter Paul and Mary – another Grossman act): “Personally, artistically and in a business sense, Albert Grossman was the sole reason Bob Dylan made it.”

PP&M’s version of Blowin’ in the Wind helped make Bob Dylan a protest icon (and a lot of money – though much more for Grossman). Part of Dylan’s journey included some topical songs that never made it far beyond the Witmark archive.

The Death of Emmett Till is such a significant song in Bob Dylan’s early catalogue, it’s astonishing to realize that most fans wouldn’t have heard him sing it. Aside from the Folksingers Choice radio show performance, the only other recording seems to be the Witmark demo.

Backed by a melody similar to his/Van Ronk’s House of the Rising Sun, Emmett Till is one of the first Dylan songs to deal with racism in America as he recounts the brutal murder of the titular black teenager and castigates Jim Crow and the KKK.

Long Ago, Far Away looks back to historical injustices like slavery, lynching and the crucifixion of Jesus while sarcastically suggesting that such things no longer happen, “DO THEY?” It’s like a proto With God on our Side.

We also get to hear early versions of some of his other protest classics like Masters of War and The Ballad of Hollis Brown, whose title was wisely updated from this version’s The Rise and Fall of…

I think the demo of Oxford Town is even better than the version that made The Freewheelin’. Dylan’s voice is great and the guitar sounds really rich for a demo recording.

Dylan’s vindictive side comes to the fore on I’d Hate to Be You on That Dreadful Day. Though he undercuts the judgemental, end-of-days vibe at the end by cheerily calling the song his “calypso tap number”.

Speaking of the apocalypse, while many of the Witmark demos are hurried, run-throughs just to get the melody and words down on tape, Dylan performs A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall with the intensity it deserves.

The demo versions of The Times They Are a-Changin’ and When the Ship Comes In previously appeared on Bootleg Vol. 1. They’re both worth revisiting as Dylan plays them on piano and while Times is a bit loose, Ship is fantastic.

And in a neat reversal, the piano that we heard on the Bootleg Vol. 1 version of Paths of Victory becomes a guitar on the Witmark demo. This version is not as jaunty and subsequently feels less triumphant.

The album The Times They Are a-Changin’ typecast Dylan as a protest singer. And these demos show that he certainly mined this seam in 1963. But he also remained interested in other topics and song styles.

25 of the 47 songs on The Witmark Demos were recorded in 1963. Songs were flowing out of Dylan and we get to hear the demo versions of classics like Don’t Think Twice, Boots of Spanish Leather and Girl from the North Country.

An amusing example of his productivity is All Over You. Dave Van Ronk said that some guy challenged Dylan, the “hotshot songwriter” to write a song with ”all over you” as the refrain. 24 hours later, Dylan played him this song and won $20.

Long Time Gone and Gypsy Lou are both blues-inflected, rambling songs, that mention a variety of American place names. The young Dylan was still portraying himself as the weary road warrior.

Gospel influences feature on both Whatcha Gonna Do? and the truncated Ain’t Gonna Grieve. The former was also recorded during the Freewheelin’ sessions but that outtake hasn’t been officially released.

Hero Blues is another lost song from The Freewheelin’, which Dylan also attempted while recording The Times They Are a-Changin’ He obviously liked this comical song as he briefly resurrected it during his 1974 tour with The Band.

Other demo versions of songs also recorded during The Freewheelin’ sessions include the fun Baby I’m in the Mood For You – which first appeared on the 1985 Biograph compilation – the gravely blues of Quit Your Low Down Ways and the uplifting Walking Down the Line, both of which were on Bootleg Vol. 1.

Plus, we get demo versions of songs that did make it onto The Freewheelin’: a ragged Bob Dylan’s Blues and a nice performance of Bob Dylan’s Dream.

While the lyrics to Guess I’m Doing Fine are very blues, the music and guitar playing are a bit more country than we’ve heard from Dylan so far. Recorded in 1964, it’s a long way from the more complex stories he’d begun telling on Another Side of…

Mr. Tambourine Man was originally attempted during Another Side’s sloshed and rushed recording session. On The Witmark Demos, we get a piano accompaniment that is a little plodding and a vocal whose weariness isn’t all that amazing.

Dylan’s voice also sounds tired on Mama You Been On My Mind, another song that he left off Another Side… But here his croak works for this lovely lovelorn piece.

The Witmark Demos concludes with I’ll Keep it with Mine – a song previously heard on Bootleg Vol. 2 as a Blonde on Blonde outtake. The sound quality on this 1964 demo is poor. Dylan would wait a couple of years before attempting to record it properly.

A strength of The Witmark Demos is that you often get insights into how Dylan feels about songs. Whether that’s sitting on them like I’ll Keep it with Mine or how he sometimes loses interest.

The high quality of the outtakes and rarities collected on Bootleg Vol. 1 makes it accessible for even casual Dylan listeners. Vol. 9 – The Witmark Demos covers a similar period and many of the same songs, but is more suited to the obsessed.

The obvious issue is that these are demos, so Dylan is naturally more casual about how he performs the songs. The demo of Only a Hobo is nice but lacks the compassion and sorrow he gave it when recording the song during the Times album sessions.

One of the highlights of Bootleg Vol. 1 is Let Me Die in my Footsteps. When recording the same song for Witmark, Dylan cuts it short and asks if they really want it. “It’s an awful drag – I’ve just sung it so many times”.

Dylan interrupts another song – Bound to Lose, Bound to Win – because he can’t remember all the verses and promises to write them out later.

He does the same on I Shall Be Free, the talkin’ blues song that appears on The Freewheelin’. “That’s about all I can remember without my notebook.”

But the big difference between Bootleg Vol. 1 and this Vol.9 is the strength of the previously unreleased songs. For me, a prime example of the (unstandably) lesser quality of The Witmark Demos is Farewell.

Written in London during the winter 1962, Farewell is a reworking of the British folk standard, The Leaving of Liverpool. Dylan’s version has been recorded by many other artists, including Judy Collins, Tim Buckley, Lonnie Donegan and Liam Clancy.

Unusually for Dylan, he doesn’t add much to this interpretation. Even when his other musical appropriations warranted a settlement with the original artist – see Jean Ritchie and Nottnum Town – Dylan’s words radically altered the new song.

But Farewell is based on a song about leaving and continues to be a song about leaving without taking any other departures from the original. For all that early Dylan has been accused of plagiarism, he very rarely failed to put his own stamp on the sources of his inspiration.

The Cohen Brothers used Farewell as the song played by their Dylan character at the end of Inside Llewyn Davis. The poor titular folk wannabe never had a chance of making it if he’s even upstaged by mediocre Bob.

Overall, The Bootleg Series Vol. 9 – The Witmark Demos (1962-64) is a fascinating document of a developing songwriter and performer. But aside from Tomorrow is a Long Time and maybe the demo of Oxford Town, there’s not enough to keep me coming back.