<< Back to Blog

Dylan Revisited: Another Side of Bob Dylan (1964)

In mid-1964, Columbia Records urged Bob Dylan back into the studio. The label was keen to capitalize on the commercial and critical success of The Times They Are A-Changin’, which was released in January of that year. Dylan obliged but, as ever, did so on his own terms.

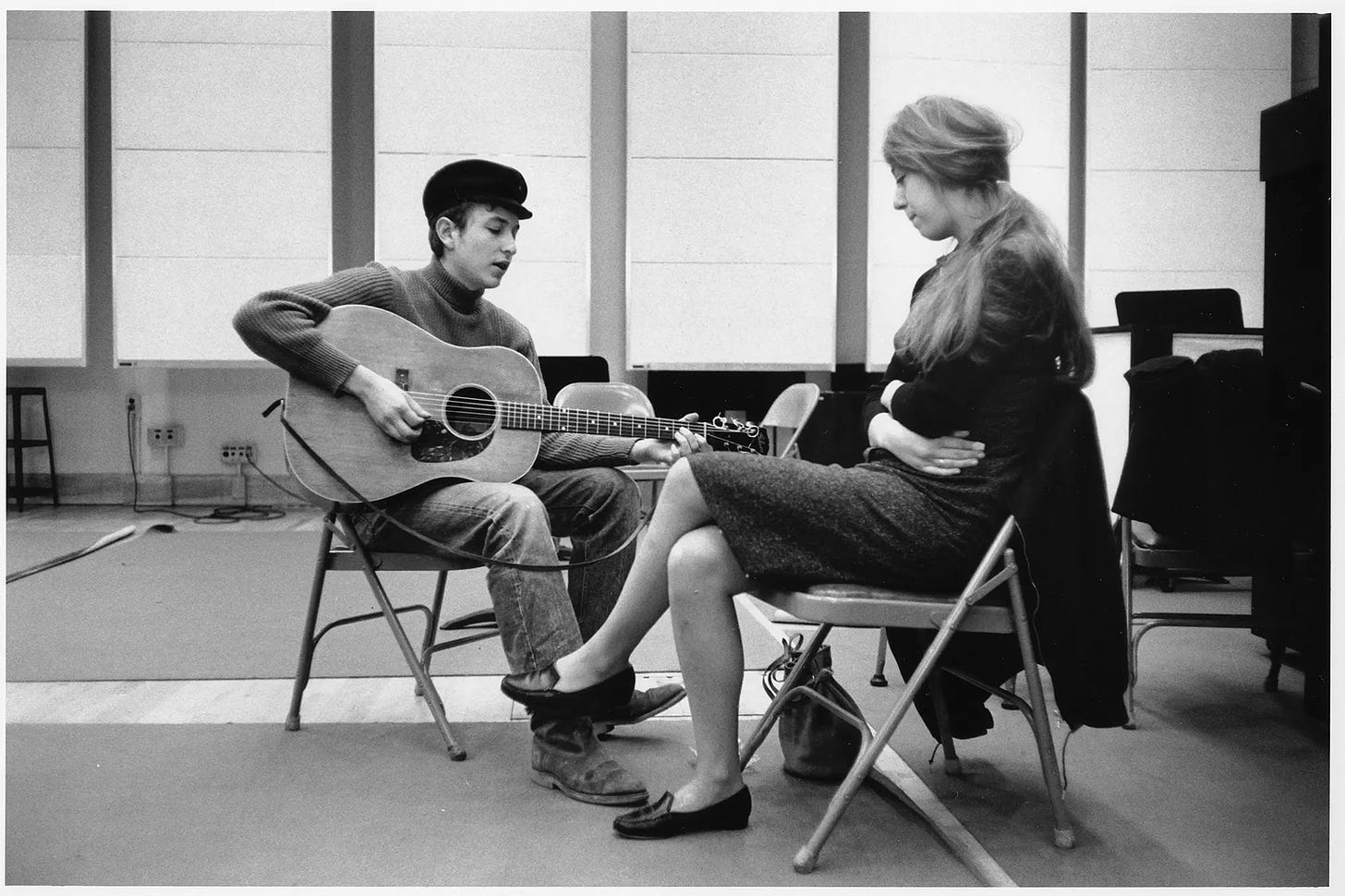

Another Side of Bob Dylan as a contractual obligation is an idea supported by the rushed recording process. After spending a week in a tiny Greek village with the pre-Velvets Nico, Dylan returned to New York and headed straight from the airport to Columbia’s Studio A.

Waiting there was producer Tom Wilson – who had no idea what to expect – some of Dylan’s friends, journalist Nat Hentoff and many bottles of Beaujolais. Over one evening, Dylan would record an album of 11 songs, most of which he had written or finished during his week in Greece.

You can hear Another Side’s loose, get-it-done vibe on its opening song, All I Really Wanna Do. Dylan does it in one take, meaning we get to hear all the mistakes, mic popping and mirth. Oh, and there’s yodeling.

Contrast this throwaway beginning to the anthemic openers of his previous two albums (Blowin’ in the Wind / The Times They Are A-Changin’) and you sense that Dylan may be making a point here. There’s protesting in this song but it’s a personal campaign.

While All I Really Wanna Do is somewhat slight Dylan song, the intensity of the rhyming throughout demonstrates that it’s still a strong piece of writing. Both Cher and The Byrds covered it, releasing their singles at the same time.

When Cher’s version became a top 20 hit in the US, Dylan teased Roger McGuinn, saying “they beat you man.” Poor McGuinn interpreted this as the songwriter feeling let down by the “protectors of his music”, but I suspect Dylan didn’t really care as long as he got paid.

Photo by Michael Ochs

Another Side of Bob Dylan features more unintended laughter during I Don’t Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Have Met). The chuckles occur when Dylan realizes he’s started singing the wrong verse from the version he had written down.

The finger-picked intro to I Don’t Believe You references the Greek folk music that Dylan must have heard during his week in the Mediterranean sun. It’s another offhand performance, which perfectly captures the theme of a fine song that he’ll continue to play live for years to come.

With its story of a woman who later blanks her former lover, I Don’t Believe You is a precursor to the vicious character assassinations electric Dylan will be writing in a couple of years. And of course, he’ll use the song’s title as part of his retort to the “Judas” catcall.

Another Side of Bob Dylan’s looseness and laughter is a stark contrast to the studied and serious, The Times They Are A-Changin’. With its yodeling, honky tonk piano and lines like “weird monkey, very funky”, this carefree record pointedly forsakes the focused, finger-pointing of his previous album.

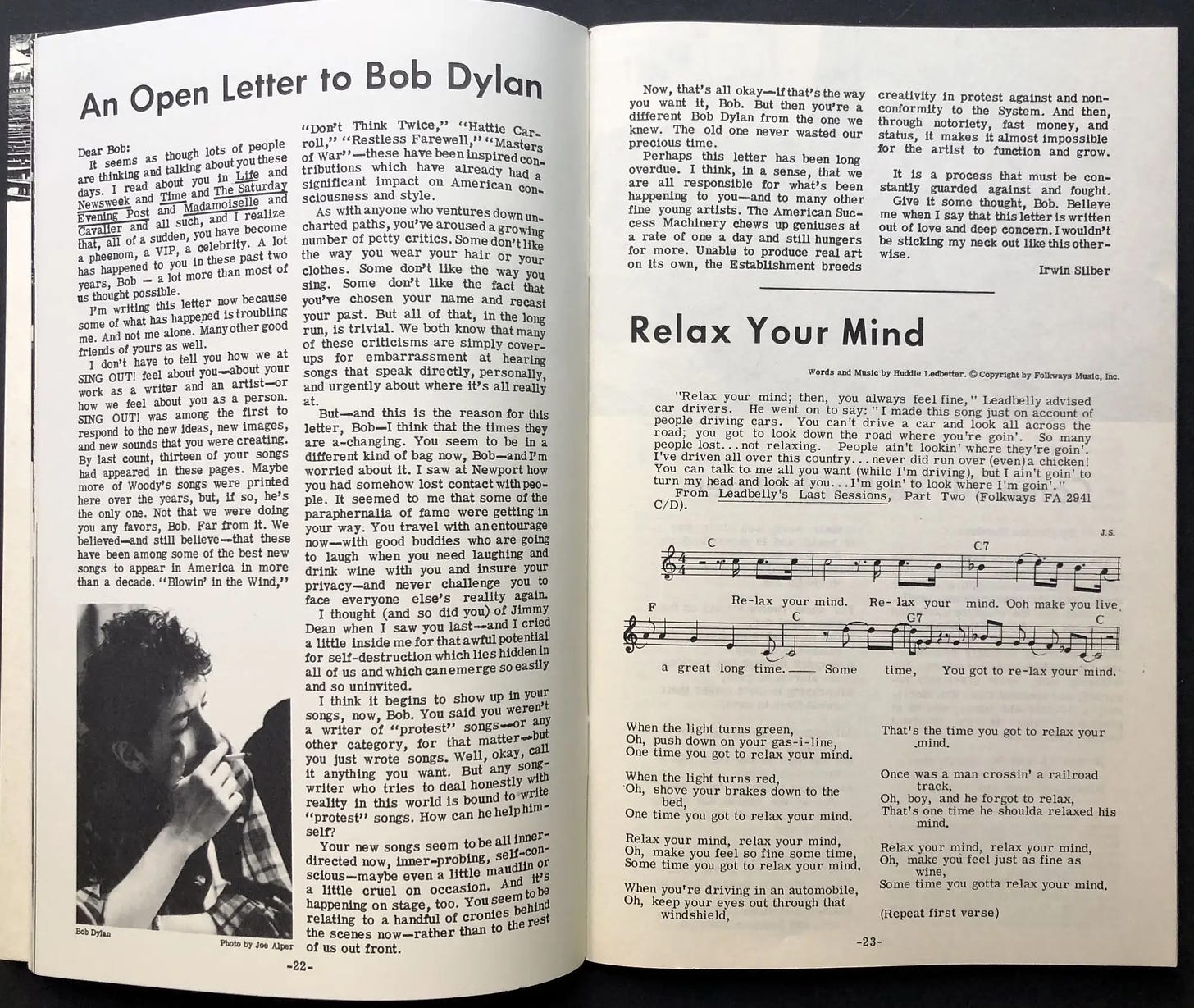

This dismayed many in the protest set, including writer Irwin Silber. In an infamous open letter in Sing Out! magazine, he warned Dylan about the perils of fame and bemoaned the lack of social concern on his new songs, saying this new Bob Dylan “wasted our precious time”.

As Another Side’s title suggests, this shift was deliberate, yet not necessarily out of character. The title was producer Tom Wilson’s idea, though Dylan didn’t think he was doing anything different. Far from being an unprecedented sighting of a different Bob Dylan, I think the album often harks back to his Freewheelin’ days.

Another Side even has I Shall Be Free #10, a sequel of sorts to the silly, jokey song of the same numberless name on Freewheelin’. This is where we meet that weird monkey, along with high-heeled sneakers, Cassius Clay and Barry Goldwater among others.

I Shall Be Free #10 has some good one-liners, even if, like many humour songs, they lose their impact on repeated listening. When I first heard the song as a teenager, I thought it was brilliantly weird and funny. These days, it feels much more disposable.

Another parallel with Freewheelin’ is Motorpsycho Nightmare. This tall tale of a narrator taking shelter with an angry farmer and his daughter Rita, is Another Side’s less apocalyptic Talkin’ World War III Blues.

The song is steeped in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 movie, Psycho. Rita appears by the singer’s bedside “looking just like Tony Perkins” and later gets a job in a motel. The conclusion that “without freedom of speech I might be in the swamp” alludes to where the psycho dumps the car of his victim.

Rita also “looked like she stepped out of La Dolce Vita”, the Fellini film in which Dylan’s Greece companion Nico had a small role. Motorpsycho Nightmare is another initially amusing but musically forgettable song that Dylan has never played live.

The recording of Motorpsycho Nightmare included the first hints of tension between Dylan and Tom Wilson. When one of the singer’s entourage suggested dimming the lights to enhance the mood, the frustrated producer shot back “we don’t need atmosphere, we need legibility”.

Another Side also features the return to the foreground of someone who was all over The Freewheelin’, as Dylan once again dredges through the ruins of his relationship with Suze Rotolo.

While her presence is felt on The Time They Are A-Changin’s few songs about love, Suze is not the focus of that record as she was on The Freewheelin’. But Another Side of Bob Dylan returns to her with greater candor that ever.

She could certainly be the “long lost lover” lamented on Black Crow Blues. Though Another Side’s second song is more memorable as the first time Dylan plays piano on an album and he goes in hard with a rocking, boogie-woogie style.

Suze is definitely present on the album’s second-last song, the eight-minute epic, Ballad in Plain D. It’s the story of an argument between the singer and the sister of his girlfriend – in real life, Carla Rotolo.

Suze later confirmed that Ballad in Plain D is based on a bust-up that happened during their break-up, likely over his affair with Joan Baez. Dylan’s version is candid, defensive and often distasteful, as when he sings about Carla: “for her parasite sister I had no respect”.

To be fair to Dylan, he later regretted the nasty side of Ballad of Plain D, saying “I must have been a real schmuck to write that.” Suze was more forgiving about his need to deal with the events in song, saying: “His art was his outlet, his exorcism. It was healthy.”

Aside from the unpleasantness, Ballad in Plain D is too long and tedious. And though many laud the final verse that asks, “are birds free from the chains of the skyway?”, saying such a self-pitying thing (even most mysteriously) to actual prisoners is a dick move.

Another Side of Bob Dylan concludes with the classic, It Ain’t Me Babe. From the opening “go way from my window” request to the plea of the title, it sounds like he may finally be leaving Suze behind.

After the trauma of Ballad in Plain D, this is Dylan drawing a line under the relationship by assuring his ex-lover that he’s not the right person for her. Though that idea is somewhat undercut by the final verse’s sly “and anyway I’m not alone”.

Another song from this album that Dylan will continue to play live, It Ain’t Me Babe might also be directed at more than just a former lover. As the focus of his lyrics become more introspective, is he also speaking to the folk crowd that see him as their messiah of protest?

On Another Side, he sings about anything but social issues. It’s the beginning of the end for Bob Dylan as a protest singer and he confronts this shift directly – albeit using oblique symbolist language – in one of the record’s most significant songs.

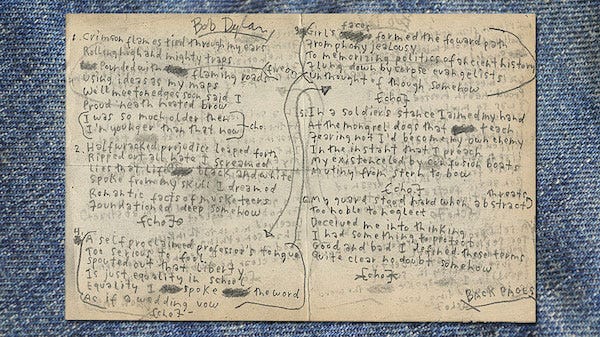

My Back Pages is the final song that Dylan recorded for the album. He uses it to address his rejection of topical songs and to torch his protest icon status with a crimson flame. It’s the sound of Dylan reclaiming himself from the folk crowd.

He explained to journalist Nat Hentoff during the Another Sessions that “I don’t want to write for people anymore. You know, be a spokesman.” In My Back Pages, he dismisses his past self as a romantic who believed “lies that life is black and white”.

Throughout an erratic but powerful performance, Dylan rejects the certainty of finger-pointing. Ironically, he does it using a tune that references his own exemplar of the genre, The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll.

The refrain “I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now” suggests Dylan has moved past the assumed wisdom of his older protest age. It’s an idea he also explored in his controversial acceptance speech for the Tom Paine Award.

It also feels like Dylan wanted to draw a line under the issue. After recording the song, it would be more than 20 years before he’d return to My Back Pages, finally playing it live for the first time at the Shoreline Amphitheatre in 1988.

But if Another Side of Bob Dylan was the singer trying to get away from being a topical songwriter, the album probably shouldn’t have included one of his best socially-inclined songs, the superlative, Chimes of Freedom.

Written just after The Times They Are A-Changin’ was released, Chimes of Freedom fits the mould of that album’s concern for the plight of the underdog, the luckless, the outcast, the aching ones and more. It’s often described as Dylan’s Sermon on the Mount.

But the rich, expansive phrasing reflects Dylan’s new lyrical direction. Each verse begins by describing a “wild ripping” storm with its “majestic bells of bolts” and “hypnotic splattered mist”. It’s luxuriant language. These are words to sink into and savor.

Dylan played Chimes of Freedom live four times in 1964 then stopped until 1987. It’s since become an on-and-off staple of his shows. Bruce Springsteen also harnessed the live power of the song with his remarkable version.

Dylan’s friend Tony Glover had reservations over the lyrics of The Times They Are A-Changin’. His reaction to Another Side was “that’s more like it”. Dylan was no longer trying to be a spokesman for people with “axes to grind”.

If Bob Dylan’s fourth album really does present Another Side to the man, it’s the increasing influence of symbolist poets like Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine and, especially, Arthur Rimbaud.

Jean Moréas’ Symbolist Manifesto proclaims a hostility to “matter-of-fact descriptions”. Instead, life should be represented through “veiled reflections of the senses”. Dylan applies this technique to philosophical songs like My Back Pages and is equally adept about love.

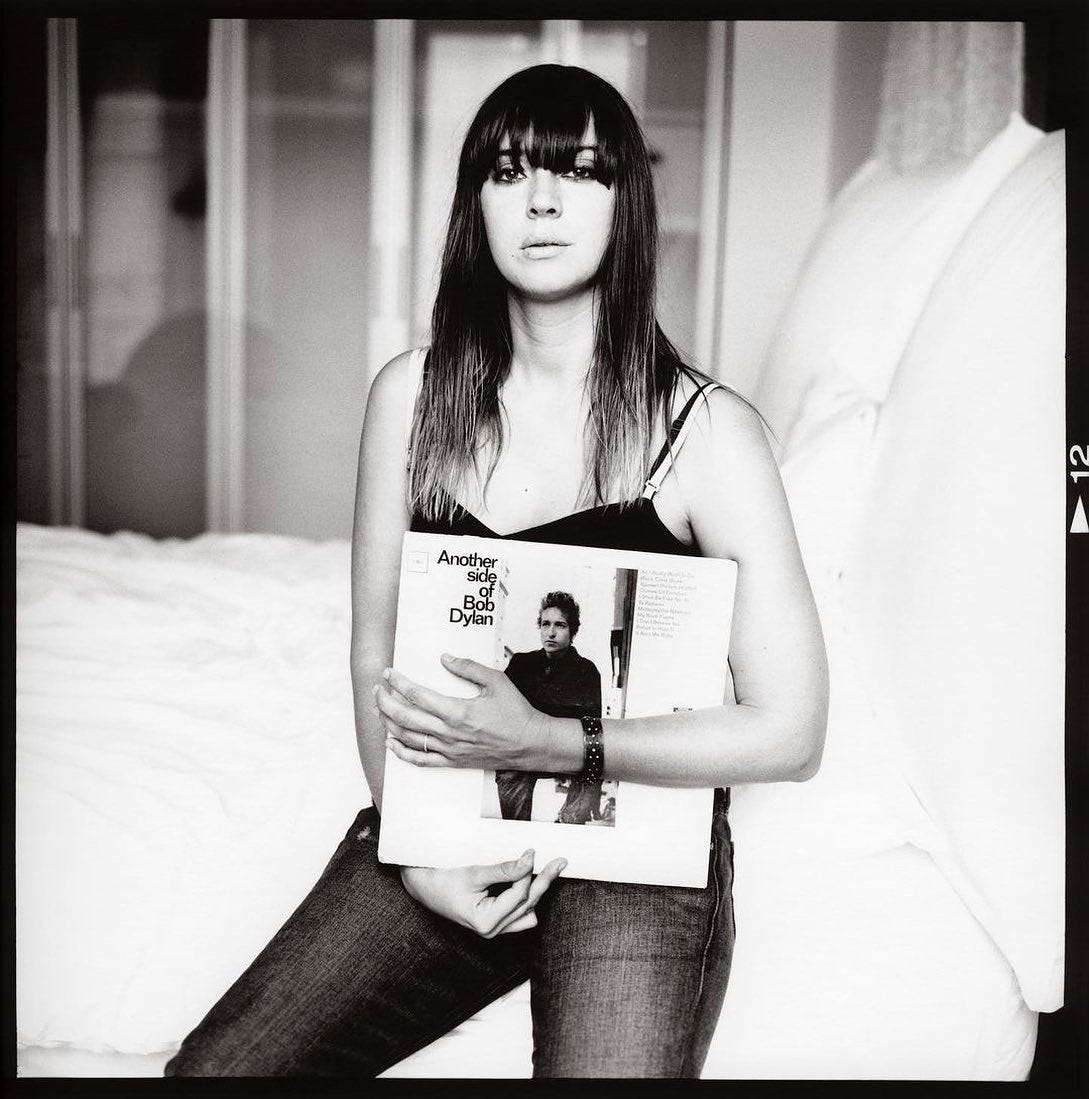

Photo: Cat Power by Mathieu Zazzo

Spanish Harlem Incident is like his symbolist proving ground. The song is essentially about an encounter with an enthralling gypsy woman that Dylan embellishes with some sublime imagery.

He asks the woman to “take me into the reach of your rattling drums” and talks about “the cliffs of your wildcat charms”. But even more notable than the lyrics, is his performance. Dylan sings the hell of out of Spanish Harlem Incident.

Dylan only played Spanish Harlem live once and will later claim to have no idea what it’s about. This lovely song seems like a mere practice run for his new style. He also tried but rejected a version of Mr. Tambourine Man during this session.

Far more durable is To Ramona, a glorious folk waltz recorded in one take that Bob Dylan has called one of his favourite songs. I’m with Bob. It’s certainly up there as one of mine.

It’s an odd love song as it features few great declarations of affection. But the complex Ramona – full of contradiction, intricacy and ambiguity – is obviously someone Dylan has thought about a lot. If that’s not love, then what is?

To Ramona adheres to the symbolist philosophy of sensory reflection with remarkable lines like: “your magnetic movements still capture the minutes I’m in” “the flowers of the city through breathlike get deathlike at times”.

Joan Baez claimed that the song is about her, as Dylan used to call her Ramona. Maybe “it’s all just a dream babe, a vacuum, a scheme babe” refers to her continued involvement in the folk scene he’s leaving behind. Or perhaps the entire song is a kiss-off to that crowd.

While Spanish Harlem and To Ramona are not as weighty as Another Side’s big hitters, My Back Pages and Chimes, they show us where Dylan is headed. A much more significant side of Bob Dylan is imminent and it will be enhanced by some loquaciously brilliant love songs.

Another Side of Bob Dylan is as inconsistent and scruffy as you’d expect from an album written and recorded so quickly. Yet it features at least four songs that I consider true Dylan classics. This is still a songwriter at the peak of his powers.

I also have a particular personal affection for Another Side…, as it was one of the first Bob Dylan albums I ever listened to. A schoolfriend lent me a cassette copy and I played it to death for a few weeks before reluctantly returning it.

What do you think of Another Side of Bob Dylan? Do you embrace the chaos or feel it has too many skippable songs? Let me know in the comments.